I have no pretentions of having an objective view, or even a particularly well informed one.

Wednesday 24 June 2015

Video Game Details: Gunpoint's brilliant animation

Oh boy, Gunpoint. I'll likely have an "In Praise Of:" post for this game at some point because it's utterly brilliant in it's entirety. Any individual detail merits a post, but I'm going to talk only about one. While the art style, music and writing are all reasons I bought the game, one of the biggest deciding factors was a really small detail, one that exemplifies in my view the style of humour Gunpoint has going for it: the falling animation.

In Gunpoint you jump by holding the mouse button and charge the strength of the jump (up to a point) for as long as you hold the M1 key down. When you release you jump, following the parabolic arc represented (in the above image) by the dots on screen.

Do you see the playable character (Richard Conway) there? He just flung himself from a building. Now, at the apex of his arc, he is in the superman pose. Brilliant. Are you in love yet? No? Take a gander down here then.

See the way that little trench coat is flapping upwards with the air resistance? Isn't that just beautiful. Still not convinced? Well, this isn't the punchline quite yet.

*plaf* That's about the best way I can describe the (wonderful) sound you make as you fall flat on your face. A core mechanic in the game (that is that you take no fall damage, as well as your ability to perform massive jumps) is explained away by Conway possessing a special pair of trousers that have some sort of springs in them. Then to test them he jumps out his apartment window and he is flat on his face, just like in the image above. The game wonderfully makes fun of it's silly explanation of core mechanics and creates a fantastic visual gag at the same time, and this tiny detail is just one of the reasons I think Gunpoint is as good, if not better than, some of the indie heavyweights (for example Super Meat Boy, Hotline Miami, FTL) and one of my all time favourite games in general.

Tremendously fun, it remains the only game I've ever wished I paid more for than I did (I bought it during a steam sale). And if I had to pick the one quality amongst so many brilliant individual elements that made me fall in love with the game; this tiny animation would be it.

Labels:

Art Style,

Francis,

Game,

Gunpoint,

Independent,

Indie,

Pixel,

Tom,

Video games

Tuesday 23 June 2015

Between The Lines: the 13 1/2 lives of Captain Bluebear

"People usually start life by being born." With that line, the book begins; an odd line to begin on and a wonderful introduction to the pure, joyous absurdity that follows. Stylistically similar to Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy the book, written by Walter Moers, follows the life (or rather the first 13 and a half lives) of Bluebear; from his discovery by the minipirates that found him floating in a walnut shell towards the edge of the greatest whirlpool to ever exist to his tenure as the greatest living congladiator and the magnificent lies that he told to claim this title. Told in the past tense, but with only the knowledge of the time, bar occasional dips into the encyclopedia in Bluebears head, the novel is written in first person and delights in the most elaborate and fantastical adventures one could ever imagine.

More than just a fantastical children's tale the book combines metaphors (grand and small), morality tales and adult ideas (although well hidden ones that likely no child under 12 would pick up on) with wonderful illustrations (also by Walter Moers) and a hefty size (just over 700 pages). Despite it's size its incredibly easy to read, with great use of different fonts, pictures, diagrams and visual emphasis of the likes of Onomatopoeia with various formatting choices, letter spacing and page by page build ups of size and font. Essentially the feeling created is that of a drawing, even when it's merely text, which makes sense as Moers is also a well reputed cartoonist.

The reason I really love this book though, although inclusive of all these details, are the clever metaphors for developmental milestones and real world feelings to bizarre happenings in a fictional world; be it the way friends drift in and out of your life, the way you only suddenly seem to notice your aging or ways in which certain relationships can be toxic and harmful while others are healthy and fulfilling, to name but a few of the more obvious ones, but both of the subsequent readings after the first revealed more parallels and moral messages that I hadn't noticed on first reading, a sign of a great book if ever I saw (read) one. There's not much more to say without heading into spoiler territory, so I urge you to pick this book up for yourself and give it a read if you haven't already, it's tremendously enjoyable (or at least I imagine it to be) for people of any age.

Labels:

13 1/2,

Bluebear,

Book,

Captain,

Characters,

fantasy,

Illustrated,

lives,

metaphor,

Novel

Thursday 18 June 2015

In Praise Of: Hotline Miami

Hotline Miami: driving soundtrack, neon-drenched visuals, sickening violence and one of the most clever narratives ever put into a video game.

A little context might be in order; I'm not a particularly big fan of violence in most media, but I don't have any particular issues with it, bar in a few particular circumstances. With this in mind I came in to Hotline Miami unsure as to what my reaction would be; the soundtrack and art style appealed to me greatly in the trailers and reviews, while the violence left me unsettled. These reactions did not change much, but the strong narrative caught me by surprise, no one seemed to mention it in initial reviews beyond that it was abstract, or hard to follow, which to me seemed one of the few criticisms the game received. The narrative is certainly abstract, but what is going on on the screen is not the only narrative; there is something going on between the game and you as the player, something I believe is directly referenced and addressed throughout the game.

That line in the image above is not directed at "Jacket" as I see it, but rather at you as the player; it directly questions your motives for murdering the people the game tells you to murder, the game certainly doesn't give you much context (or any, in the beginning). It questions why you are enjoying what is essentially a spree of hyper-violence; and I love it for that. Games have, for a long time, reveled in pure game play, eschewing narratives entirely due to a perception that they are not required. Everyone knows that the little space ship in Space Invaders is the 'good guy', the aliens at the top 'bad guys' and such was the state of it; shoot everything that moves, get points, move on.

Spec Ops: The Line and Hotline Miami represent a newly emerging attitude towards the violence we engage in for entertainment, one that criticises the way we blindly accept our motives and are perfectly OK with everything that happens afterwards so long as it is justified. Spec Ops is of course criticising warfare in general and is at least partially based on or inspired by Heart of Darkness, and while I think both games make their criticisms in different and effective ways there is one particular element that separates the two: the element of choice. Spec Ops' most infamous scene (the white phosphorus sequence) is a false choice; in order to complete the objective and to save civilians (or so you are told) you have to use white phosphorus; there is no other option; something that leaves the reveal afterward feeling a little hollow. Hotline Miami on the other hand nails it with clever design decisions. After introducing the game's mechanics in a most unsettling manner (establishing a baseline for the impact of the violence, something also done in Spec Ops) before disguising this impact under something else; a purpose (again, something both games do), in the case of Hotline Miami the first, and only objective you receive is to take a briefcase. After you talk with three masked figures in a surreal sequence there is one, essential part to Hotline Miami that makes the subsequent questioning of your morals mean something; you begin in your house. A fairly innocuous detail on the surface, but one with greater implications: you never needed to kill these people, you chose to. You left the house. You continued to leave the house on future occasions. You killed these people, because just staying in the apartment wasn't enough for you, because you wanted game play, and that small distinction makes Hotline Miami what it is, because it makes you want to kill these people, before it ever questioned you for doing so, through a fantastic array of reward systems.

Firstly the music is rewarding you as you play; thumping 80s synth and electronica driving you through each level. On top of this is a scoring system that rewards fast gameplay with combos and greater violence netting higher scores, flashing lights in bright colours and large numbers highlighting recent victims. Because of this emphasis on fast, twitchy game play your attention is never focused on what it is you're actually doing, and acts that made me a little sick to my stomach at times go by almost unnoticed in a frenzy of top-down, tightly executed combat.

Then the level is over and the reward systems aren't there anymore; the music has stopped and been replaced by an eerie drone and the only thing left to do is find your way out via the way you came, wading through the gore you so recently created and all of a sudden that sickening feeling, established in the tutorial, returns, you see what you've done and you acknowledge that at the time you were enjoying yourself. Through this the game brilliantly manipulates your preconceptions of reward systems and your expectation of associated moral justification to create an unsettling statement on the violence we so readily consume, even if it is, as the game loves to remind us, just a game; are we really OK with just accepting that we'll commit horrible acts of violence just because we are told to, and does it even matter if the violence is justified?

Hotline Miami is more than just an excellent soundtrack and fantastic game play, it's a game that's not afraid to question you as the player, to question your motives, but also why you might look for them; not afraid to create a message about violence in games (and perhaps in media in general) while being itself an extremely violent game. A master class in creating meaningful reward systems and linking game play to story beats, Hotline Miami is an absolute masterstroke.

Tuesday 16 June 2015

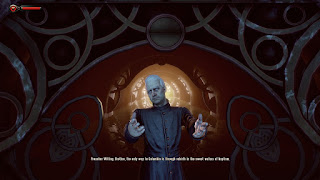

Video Game Details: Bioshock Infinite's most dangerous locale

Firstly a quick message: As the second post to this blog, I thought I'd make the exact opposite to my first post; as well as give a bit of an idea how I will approach posts in future. Grinding My Gears in my mind will be an occasional series with writing about things in entertainment and media that are irritating me, typically with a slightly more serious bent. Video Game Details will consist of shorter, more silly posts spotlighting details in Game design and their brilliance or stupidity (or both in the right situations). I've got more plans for other regular posts which I'll reveal as I go, if you've got any recommendations or criticisms leave a comment, I'll read all of them.

Bioshock Infinite's Columbia is pretty heavy on symbolism and arguably the biggest, bar the lighthouses that feature prominently in the final sequence, is Baptism (and related concepts of course). As such water features quite prominently, most noticeable in the opening sequence: water covers the floors, offering reflections of the candles and stained glass windows that make up the area. The first dream like moment was induced by near drowning during a baptism, but in reality you'd find it hard to make it that far alive.

What am I talking about? The fact you'd likely die during the initial ascent? The fact that any town quite as paranoid about an intruder as clearly branded as Booker would have a guard when you first arrive at the Church like entrance? No, but both of those would be far more legitimate reasons than the one I'll discuss (and far to legitimate for these posts). No, I'm talking about the poor design of the area's plumbing and the staircase that would likely leave you in a broken pile at the bottom.

Sure, it might look nice, having an endless stream of water running down a stone staircase lit only by the occasional window and a quantity of candles significantly larger than anyone could realistically replace each day, but that is one hell of a dangerous staircase if ever I saw one.

Notice that this system isn't only dangerous for you, new visitors or the constant rotation of candle-replacers that must inevitably populate this church, but also for the priest/ official welcome. He is standing in robes that are wet, constrictive and likely heavy and is expected to walk down these poorly lit stone steps with a constant stream of water running down them? Perhaps this is Father Comstock's notion for population control, or an underpaid architect's petty revenge, but truly this pretty little introduction would cause more than a few issues in the real world.

Saturday 13 June 2015

Grinding My Gears: GoT has an issue with female characters

Daenerys. Brienne. Cersei. Three major characters with different backgrounds and different perspectives, but all defined by the same thing: they are women.

To be clear; I like Game of Thrones, both the books and the TV show (although in the interest of the audience I will only be discussing the TV series, don't read anything if you're not completely up to date though, spoilers may be discussed) but both seem to have an issue writing for female characters, with the exception of only a few.

Take Daenerys as an example; she's undoubtedly strong, willful and capable, however despite being, or desiring to be, depending on the point in the narrative, queen she seems to spend the majority of her time in traditionally female roles; she is wife to Khal Drogo and a literal bargaining chip for her brother, when she achieves power she is naive and kind; a typical character trait for a young woman, while not such an issue by itself, when paired with the role she assumes as 'mysha' later in the plot this trend becomes a little more odious. Here she fills an even bigger stereotype; that of the mother; a role she is obsessed with, labeling herself mother of dragons and referring to those she presides over as her children. Although it is perhaps understandable, or perhaps natural, for her character arc after losing her child, it seems at the least clumsily done, and at worst a terrible amalgamation of cliched notions of femininity; notions that certainly crop up again in the character of Cersei.

Cersei is about as black and white as it gets; all she cares about is her children, herself and her identity as a woman in a man's world. Cersei, as the instigator of the plot on King Roberts life is framed from the beginning from Ned's eyes,and as such is portrayed in an extremely negative light. This is completely understandable, she did, after all, arrest the "main character" (as many saw him) at the time; Ned Stark after he, out of compassion or a sense of honour, warned her that she and her children would likely be killed once it became known they were fathered by Jaime. So if it is expected that that she is to be hated, why do I have such an issue with the way she is portrayed? Well, to illustrate my point look at Jaime; he pushed a kid out of a window to ensure the continued secrecy of his relations with Cersei and for a time I despised him; the golden child who has everything that everyone is either annoyed by or jealous of. Yet when the plot spends more time with him (it is worth noting in the books these chapters are from his point of view) one begins to understand and sympathise to an extent with his motivations. He goes from one of the most morally reprehensible characters to one that has made some major moral decisions and suffered for doing so. I personally even went some way towards forgiving his crime for his motivation; one stranger's life against the lives of his own three children; a choice that is far easier to understand and accept than it first appears. Cersei on the other hand, while having the same motivations is still reviled and despised even after more of her history and back story is revealed; a fault that, in my view, does not lie in the eyes of the audience, but in the hands of the show's (and book's) creators as she is consistently framed as the jealous step-mother, the queen who wants only to be the most beautiful; a woman who loves herself so much that when her twin brother isn't around she wants to sleep with her cousin in stead. Where Jaime's character branches out from the way in which we first view him, Cersei's character only becomes more entrenched in the negative light she is initially portrayed in. This shallowness is an affliction that impacts almost every female character in my eyes and Brienne, the conceited effort to subvert the expected roles of a woman tragically conforms to them more than any other character.

Brienne is defined by her appearence; she is tall, ugly, freakish before she is described as strong; she wanted to be pretty, wanted to be loved and married before she came to practice swordsmanship and is as obsessed with sex as the majority of her fellow female characters, albeit in another way to most others. Once again, all of these traits are not causative of a bad character, but they succumb to the traditionally female roles that Brienne is seemingly meant to subvert. As a strong, capable woman it seems an awful shame to me that she is portrayed as equally naive as Daenerys or Cersei are, and totally submissive to every other strong character she comes across. She loves Renly, admires Catelyn, seemingly loves and admires Jaime after a time but she never seems to follow her own goals; she doesn't have any other ambition but to keep promises she makes, with little other pretext for making these promises beyond her respect for these characters.

This leads in to one of the female characters that I think is a strong and well fleshed out character; Catelyn. As a character who not only cares for her Children and for people in general, who has a deep seated resentment for Jon Snow as the product of Ned's infidelity (I am well aware of the theories regarding this subject, but being from Catelyn's perspective this is fact in her eyes). Catelyn Loves Ned Stark, but not only him, her children, but not only them, her siblings and family as well, but she's not merely a compassionate or kind person to everyone; she mistrusts and dislikes as many people as she likes and she loves people in more than the binary ways of these are my children or this is my partner, she has complex relations with everyone of her family members and she is weak in some areas and strong in others. At the core of it; she's human, and feels like it. Unfortunately Catelyn, as well as Arya, Olena Tyrell, and (to a lesser extent) Sansa are the exceptions to what largely feels to be the rule. Almost every other female character spends large amounts of time talking about, engaging in or fearing sexual activity in a way that only Tyrion seems to be able to match; yet what is the purpose for all the time he spent with Shae? To shed light on his previous relationship with Tysha and his hatred for his father. Seeing Shae in this light is perhaps a little unfair; she wasn't a main character, and the importance she seemed to have stemmed from Tyrion's feelings toward her, and despite being fairly unimportant to the plot I actually thought she was one of the better female characters.

The time spent with female characters (from their perspective) and their partners however feels much emptier; Cersei has sex with Jaime, and while he's away, her cousin which only seems to tell us that she is narcissistic in the extreme, Dany is on top of Drogo; all this seems to tell us is that she is more comfortable taking agency and control in what previously seemed an opressive relationship (admittedly this has larger implications for her character arc, but a lot of time was spent leading up to this scene that could have been spent in many other ways and in my opinion more effectively), Brienne nearly gets raped, proving through her frightened reaction that she is completely normal, reacting the way anyone would in such an abhorrent circumstance. Sex seems to be a cheap way to make us care for, fear for or loath a character and for whatever reason GoT can't seem to go for more than an episode without using an innocent woman to prove that a man is evil; one of their favourite short-hand techniques to manipulate us to hate a character (see most recently Meryn Trant who we are reminded is a bad guy by his insistence on an underage, seemingly unwilling prostitute while in Braavos, or the wildling mother in Hardhome who exists only to orphan her children and give a face to the victims of the others). The rest of what seems to constitute a female character's motivations tends to boil down to on/off switches of [feelings for children or subjects (y/n)] [feelings for partner (y/n)] [desire for sex (y/n)] with the exceptions I mentioned earlier. Of course the motivations for the male characters could be boiled down to a similar set of criteria, but the male characters are never defined by their gender or the cliched notions associated with it; while the women frequently are; I don't even want to mention the sand snakes as represented by the TV series.

To re-iterate; I think GoT is an incredible TV (and book) series, but the way the female characters are dealt with often doesn't do the rest of the narrative (in both the books and TV series) justice. I certainly hope I'm wrong, and what I'm seeing is only a temporary glut in the character development of most of GoT's leading ladies, but I worry that might not be the case. This post also is obviously not an attempt to cash in on the internet traffic in the lead up to the finale. Obviously.

To be clear; I like Game of Thrones, both the books and the TV show (although in the interest of the audience I will only be discussing the TV series, don't read anything if you're not completely up to date though, spoilers may be discussed) but both seem to have an issue writing for female characters, with the exception of only a few.

Take Daenerys as an example; she's undoubtedly strong, willful and capable, however despite being, or desiring to be, depending on the point in the narrative, queen she seems to spend the majority of her time in traditionally female roles; she is wife to Khal Drogo and a literal bargaining chip for her brother, when she achieves power she is naive and kind; a typical character trait for a young woman, while not such an issue by itself, when paired with the role she assumes as 'mysha' later in the plot this trend becomes a little more odious. Here she fills an even bigger stereotype; that of the mother; a role she is obsessed with, labeling herself mother of dragons and referring to those she presides over as her children. Although it is perhaps understandable, or perhaps natural, for her character arc after losing her child, it seems at the least clumsily done, and at worst a terrible amalgamation of cliched notions of femininity; notions that certainly crop up again in the character of Cersei.

Cersei is about as black and white as it gets; all she cares about is her children, herself and her identity as a woman in a man's world. Cersei, as the instigator of the plot on King Roberts life is framed from the beginning from Ned's eyes,and as such is portrayed in an extremely negative light. This is completely understandable, she did, after all, arrest the "main character" (as many saw him) at the time; Ned Stark after he, out of compassion or a sense of honour, warned her that she and her children would likely be killed once it became known they were fathered by Jaime. So if it is expected that that she is to be hated, why do I have such an issue with the way she is portrayed? Well, to illustrate my point look at Jaime; he pushed a kid out of a window to ensure the continued secrecy of his relations with Cersei and for a time I despised him; the golden child who has everything that everyone is either annoyed by or jealous of. Yet when the plot spends more time with him (it is worth noting in the books these chapters are from his point of view) one begins to understand and sympathise to an extent with his motivations. He goes from one of the most morally reprehensible characters to one that has made some major moral decisions and suffered for doing so. I personally even went some way towards forgiving his crime for his motivation; one stranger's life against the lives of his own three children; a choice that is far easier to understand and accept than it first appears. Cersei on the other hand, while having the same motivations is still reviled and despised even after more of her history and back story is revealed; a fault that, in my view, does not lie in the eyes of the audience, but in the hands of the show's (and book's) creators as she is consistently framed as the jealous step-mother, the queen who wants only to be the most beautiful; a woman who loves herself so much that when her twin brother isn't around she wants to sleep with her cousin in stead. Where Jaime's character branches out from the way in which we first view him, Cersei's character only becomes more entrenched in the negative light she is initially portrayed in. This shallowness is an affliction that impacts almost every female character in my eyes and Brienne, the conceited effort to subvert the expected roles of a woman tragically conforms to them more than any other character.

Brienne is defined by her appearence; she is tall, ugly, freakish before she is described as strong; she wanted to be pretty, wanted to be loved and married before she came to practice swordsmanship and is as obsessed with sex as the majority of her fellow female characters, albeit in another way to most others. Once again, all of these traits are not causative of a bad character, but they succumb to the traditionally female roles that Brienne is seemingly meant to subvert. As a strong, capable woman it seems an awful shame to me that she is portrayed as equally naive as Daenerys or Cersei are, and totally submissive to every other strong character she comes across. She loves Renly, admires Catelyn, seemingly loves and admires Jaime after a time but she never seems to follow her own goals; she doesn't have any other ambition but to keep promises she makes, with little other pretext for making these promises beyond her respect for these characters.

This leads in to one of the female characters that I think is a strong and well fleshed out character; Catelyn. As a character who not only cares for her Children and for people in general, who has a deep seated resentment for Jon Snow as the product of Ned's infidelity (I am well aware of the theories regarding this subject, but being from Catelyn's perspective this is fact in her eyes). Catelyn Loves Ned Stark, but not only him, her children, but not only them, her siblings and family as well, but she's not merely a compassionate or kind person to everyone; she mistrusts and dislikes as many people as she likes and she loves people in more than the binary ways of these are my children or this is my partner, she has complex relations with everyone of her family members and she is weak in some areas and strong in others. At the core of it; she's human, and feels like it. Unfortunately Catelyn, as well as Arya, Olena Tyrell, and (to a lesser extent) Sansa are the exceptions to what largely feels to be the rule. Almost every other female character spends large amounts of time talking about, engaging in or fearing sexual activity in a way that only Tyrion seems to be able to match; yet what is the purpose for all the time he spent with Shae? To shed light on his previous relationship with Tysha and his hatred for his father. Seeing Shae in this light is perhaps a little unfair; she wasn't a main character, and the importance she seemed to have stemmed from Tyrion's feelings toward her, and despite being fairly unimportant to the plot I actually thought she was one of the better female characters.

The time spent with female characters (from their perspective) and their partners however feels much emptier; Cersei has sex with Jaime, and while he's away, her cousin which only seems to tell us that she is narcissistic in the extreme, Dany is on top of Drogo; all this seems to tell us is that she is more comfortable taking agency and control in what previously seemed an opressive relationship (admittedly this has larger implications for her character arc, but a lot of time was spent leading up to this scene that could have been spent in many other ways and in my opinion more effectively), Brienne nearly gets raped, proving through her frightened reaction that she is completely normal, reacting the way anyone would in such an abhorrent circumstance. Sex seems to be a cheap way to make us care for, fear for or loath a character and for whatever reason GoT can't seem to go for more than an episode without using an innocent woman to prove that a man is evil; one of their favourite short-hand techniques to manipulate us to hate a character (see most recently Meryn Trant who we are reminded is a bad guy by his insistence on an underage, seemingly unwilling prostitute while in Braavos, or the wildling mother in Hardhome who exists only to orphan her children and give a face to the victims of the others). The rest of what seems to constitute a female character's motivations tends to boil down to on/off switches of [feelings for children or subjects (y/n)] [feelings for partner (y/n)] [desire for sex (y/n)] with the exceptions I mentioned earlier. Of course the motivations for the male characters could be boiled down to a similar set of criteria, but the male characters are never defined by their gender or the cliched notions associated with it; while the women frequently are; I don't even want to mention the sand snakes as represented by the TV series.

To re-iterate; I think GoT is an incredible TV (and book) series, but the way the female characters are dealt with often doesn't do the rest of the narrative (in both the books and TV series) justice. I certainly hope I'm wrong, and what I'm seeing is only a temporary glut in the character development of most of GoT's leading ladies, but I worry that might not be the case. This post also is obviously not an attempt to cash in on the internet traffic in the lead up to the finale. Obviously.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)